St. Pius X and the Music Academy

by Dr. Andrew Leong

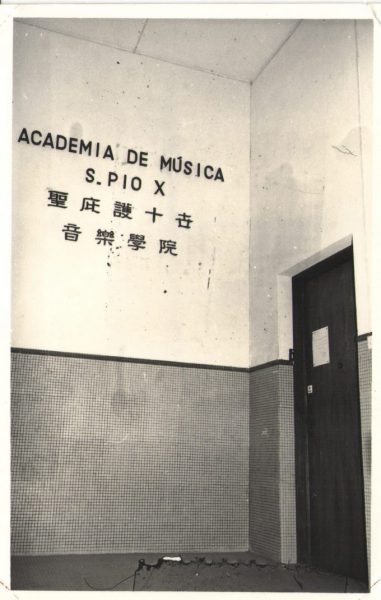

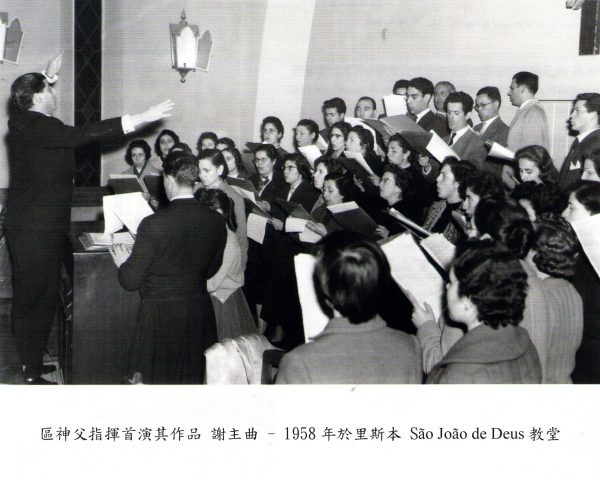

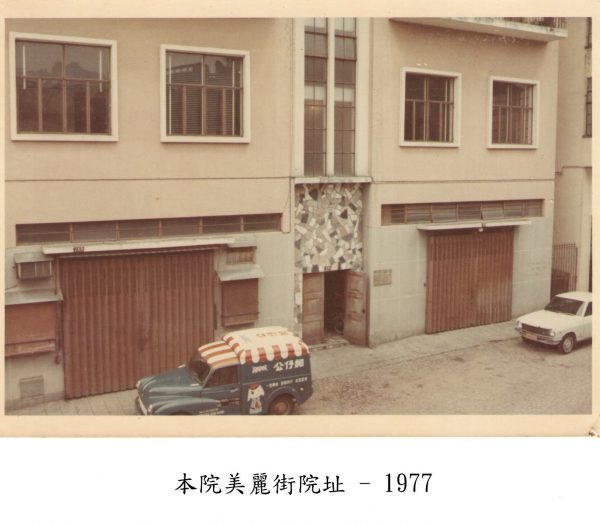

The Catholic Diocese of Macau runs an academy that offers children systematic musical formations, including piano, violin, cello, musical theory, etc. Founded in the academic year 1962/63, the music academy has been serving the communities in Macau for over half a century, and is also the first institute that provides systematic musical trainings in Macau. Fr. Áureo Castro, who founded this academy, named it St. Pius X Music Academy (officially in Portuguese: Academia de Música S. Pio X). Why did Fr. Áureo name the academy after Pope St. Pius X? And how was he related to music formation? Today, let us work out this puzzle.

St. Pius X, born Giuseppe Melchiorre Sarto, on June 2, 1835, came from a peasant family. His father, Giovanni Battista Sarto, was a village postman. Giuseppe was the second of ten children. In addition to his grassroots origin, St. Pius X’s care for the poor is also well-known. Just take one example. In 1908, an earthquake with a moment magnitude of 7.1 hit Messina, the second greatest city in Sicily, and caused a 12m high tsunami striking the coast. This catastrophe rendered both Messina and Reggio di Calabra, the city on the opposite shore, almost completely destroyed, with over 120,000 deaths, and countless people were made homeless. Hence, a huge wave of refugees fled north. In view of this, the pope not only collected donation of about 5 million francs, sending teams of nuns with medical backgrounds to serve those dioceses that took in refugees, he opened the gate of the papal palace himself, hosting about 300 refugees in his building that was at the same time housing the frescoes by Michelangelo and Raphael. Pius X also ordered the St. Martha Pontifical Hospital to accept more refugees, and arranged donation, clothes, and food to be sent the places hit by the earthquake. What is equally praiseworthy is that, after assuming his papal ministry, Pius X rejected all favours shown his family. No matter his brothers or sisters, even his most favourite nephew, all lived peasant lives like others from a grassroots origin. We may hypothesise that this insistence on simplicity also shaped St. Pius X’s philosophy of music.

To better understand St. Pius X’s view on music, it is necessary to have a look at the historical context of his time. In the 19th century, operatic style dominated the use of sacred music in Italy. Employing the beautiful modern music into church services was thought to be pleasant and pleasing. The music that was perceptible to people were those composed by the masters of the Romantic school, for example, the canticles by the Italian composers Gioachino Antonio Rossini and Saverio Mercadante, and the elaborate settings on the Mass by Charles-François Gounod, César Franck, and Luigi Cherubini. However, for most choirs, these works were too difficult. Hence, some lesser known musicians simplified these works for liturgical use, while maintaining their Romantic style. For this, they sometimes even modified the liturgical Latin lyrics so as to suit the music, or made the works more theatrical, to follow the taste of the time. In the second half of that century, this trend caused some reactions. These reformers thought that these works of sacred music had already lost their religious sentiment, could no longer touch the heart of the believers, and failed to elevate the spirit of the people. In short, they had lost their liturgical function. Therefore, the reformers proposed to revive the use of the traditional Gregorian Chant, and promoted the polyphonic compositions by the late 16th century Italian composer of the Roman school, Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina. At the time of this reaction against the Romantic style of sacred music, Giuseppe began teaching sacred music, among other subjects, in the seminary of the Diocese of Treviso.

The pursuit of Giuseppe Sarto for a more simplistic style of sacred music began to be observed first in the orders given by him as the bishop of Mantua since 1884. In 1888, he forbade the use of bands in churches, as well as the inclusion of women as members of church choirs. Certainly, the latter is today not accepted at least to some. Nevertheless, my conjecture is that this was one of the measures against using music of a theatrical style in church services. Later, in 1893, Giuseppe Sarto was named Patriarch of Venice. At this point, he further forbade singing the Tantum Ergo over theatrical tunes. Moreover, in the same year, when Pope Leo XIII was contemplating issuing a document on sacred music, he submitted a 43-page proposal. In 1903, Leo XIII died, and Giuseppe Sarto succeeded him as Pius X. After three months of his coronation as pope, he promulgated the Motu Proprio on sacred music, Tra le Sollecitudini. With this Motu Proprio, Pius X now implemented his ideal of sacred music in the global Catholic Church, including the revival of Gregorian chant (n. 3), the promotion of Renaissance polyphonic music (n. 4), the prohibition of women joining choirs (n. 14), the prohibition of the use of any instruments except the organ (nn. 15, 18; except wind instruments with the approval by the diocesan bishops, thus string instruments were totally banned, see: n. 20). Regarding modern compositions, Tra le Sollecitudini does not order a complete disuse, but those that are theatrical in style have to be avoided (nn. 5-6, see also n. 11). In addition to his promulgation of Tra le Sollecitudini only three months after his assumption of the papal office, the care of Pius X of sacred music can also be seen in his order to establish the Pontifical Institute of Sacred Music in 1910, seven years after his papal coronation. This pope, who loved sacred music so much, passed away at last on August 20, 1914. He was canonised on May 29, 1954 by Pope Pius XII.

Although not everyone today could appreciate all of St. Pius X’s ideal of sacred music, his intention of returning to a more simplistic style of sacred music is obvious to all. It is evident that he did not reject highly artistic music merely because of its technical requirements, but he envisioned an ideal of sacred music that rings in the keep of the hearts of humankind. This ideal of his, as well as his enthusiasm for music, deserves the admiration of all those who learn and play music. And I think, this is also the dream of Fr. Áureo Castro, the founding director of St. Pius X Music Academy.